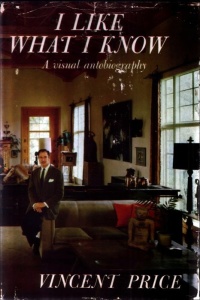

In 1959, Vincent Price recounted his life-long passion for the art world in I Like What I Know. Here are some extracts from Price’s visual autobiography, in which a 48-year-old Price reflects back on his two-day stay in Venice in August, 1928…

In 1959, Vincent Price recounted his life-long passion for the art world in I Like What I Know. Here are some extracts from Price’s visual autobiography, in which a 48-year-old Price reflects back on his two-day stay in Venice in August, 1928…

ON REACHING VENICE

‘On our itinerary Tour 22 offered no diamond in its glamorous array to touch the hope of Italy. If you’re in love with art, the honeymoon is there. All other art seems distant and a little strange without the eyes of Italy to see it through. You may have scattered affairs with other arts – deep passions, even – but the golden wedding partner is waiting for you at home in Italy.’

‘The moment came. We tool the train to Venice. Continents of natural beauties lay between: the Dolomites, the mountains, lakes, lovely towns. But dreams of Venice blinded me, and I’ll never forget, for all this poetic dreaming, the force with which the squalor of Venice hit me. On a tour like ours – so cheap, so all-inclusive – the economy was hotels. In any language, we found ourselves at the Hotel du Gare… next door to the station. This was an easy way to keep us all together, and to get us off for the next place. For comfort, nothing could compare to them. They had none. The food was miserable, the beds were hard, and the baths so involved and tepid that you almost preferred to stay dirty. But I must say they were good places with which to compare the rest of the surroundings! Almost anything looked glorious, in comparison. All over Europe they were the same – especially in color. Soot. Brown.’

‘Venice, from the station hotel, could be Hoboken with wet pavements. Arriving as we did in the dead of night, one had the suspicion that the advertised beauties of this gem of the Adriatic were elsewhere. Maybe another fourteen-hour train trip away?… Even the Venetian morning light lent little glamour to the scene around the station. You could only hope that such glamorous items such as gondolas did exist, since only some shabby, high-prowed canoes were anchored in front.’

ON ST MARK’S SQUARE

‘Sure enough, Venice did exist. We cruised down the Grand Canal and there was the Rialto, the ‘business end’ of Venus, as some wag had put it. And farther on, the canal became wider and we could see the domes of St Mark’s and the campanile, pointing above everything to that incredible blue sky.’

‘What a wonderful square that is, St Mark’s… and those damned pigeons… and those four glorious horses, prancing on the balcony; then, of course, St Mark’s lion, high on his column, looking back – keeping his eye of the pigeons. The Palace of the Doges and the Bridge of Sighs, and once again the feeling of loss that those glamorous barbarians had moved away, and other times (even if for the better) had forever exiled the pageantry of nobility.’

ON TITIAN AND TINTORETTO

‘There were two painters on the grand scale who knocked one down: Titian and, again, Tintoretto. Guardi and Canaletto certainly tell us the everyday story of their day in Venice, but Titian, in those majestic portraits, and Tintoretto, in his attempt to populate the Doges Palace with the Heavenly Host itself – sacred and profane – they were the genuine echoes of the glorious past. And Tintoretto had another quality that was almost his alone: he could paint flight. He could make a human being soar through the air, light as a bird, light as light.’

ON LEAVING VENICE IN A HURRY

‘Vence was almost too much for a sixteen-year-old, falling in love with art, and the hotel by the station, on the sewer canal, was altogether too much. So I got permission to leave the tour and go to Florence a day ahead of schedule. I took the night train alone, and naturally. I went third class…’

Find out what happened next, tomorrow.